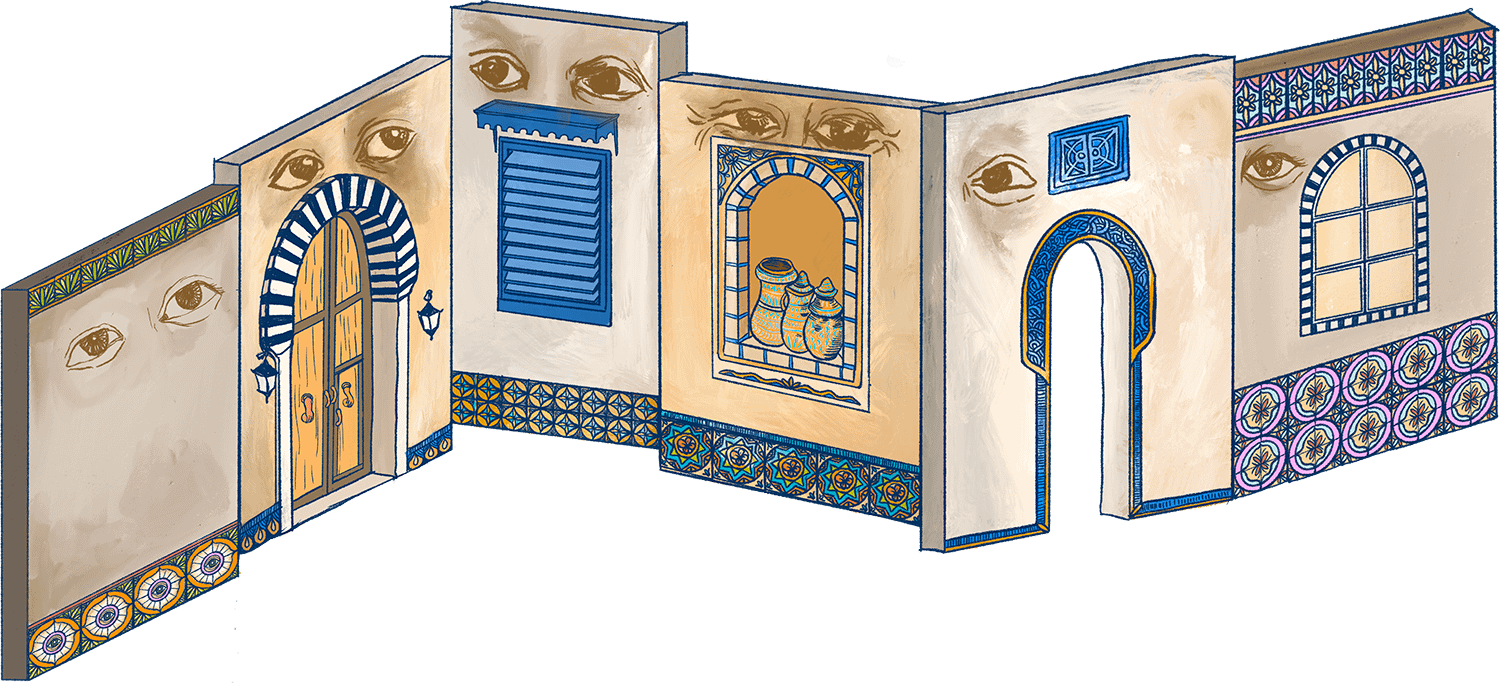

These Walls Tell Stories

Fiction | From Legends in My Blood, Book 1: Bsaies, Chapter Eight

THE CONVERSATIONS between the different walls of the house continued. House walls, those who happened to gain awareness, personalities, and the ability to converse and share stories, really do love to talk. If one ever discovers the ability to listen in to the stories and conversations of house walls, one should listen in discreetly, and simply enjoy the experience—and avoid telling others about it; people who can’t hear houses talking are bound to think that you are somewhat touched in the end, even going mad—if you insist that you hear the stories that these walls tell.

Gossiping walls of Hajj Mohamed Bsaies’ house: Zohra, the east wall; Othman, the west wall; Mabrouk, the north wall; Ramla, the west wall; Lilia and Yasmina, the interior and courtyard walls

Yasmina & Lilia’s Tale: Mad Merchant of the Medina

Then it was the turn of the twins, Yasmina and Lilia—the interior and courtyard walls to tell their story. It was something that all the other walls did not expect—and they felt sorry that Yasmina and Lilia had to go through such an incident.

“I think it was around the year 1200 or 1300, as you might remember, when that rich trader Jalal moved in here with his wife and daughter,” said Yasmina.

“Right, right,” Ramla, the west wall, interjected, “I remember them. Jalal and his wife used to have petty arguments in the bedroom but they were never the sort who would fight a lot, unlike other couples who lived here.”

“Anyway,” Yasmina continued, “this happened right about the time when the ship carrying Jalal’s goods was captured by pirates and sank off the coast near Djerba island. The poor man learned about this only when his good friend and that friend’s son—the only survivors of the tragedy—finally returned to Tunis with the news.”

Lilia then piped in to continue the tale. This was how the twins usually conversed, taking turns, each one excited to be the one to talk. “Poor Jalal collapsed in tears and started wailing upon hearing the news. Nearly his entire fortune was wiped out because of that tragedy. He became so despondent that his wife moved back to her mother’s house, taking the daughter with her, of course.

“Relatives told her to simply allow Jalal to grieve alone, that in time he would recover his wits and senses. But the days stretched on to weeks, and Jalal simply got worse. He began hallucinating, talking to unseen presences, to his dead friends and relatives, and he was just a wreck—there were days when he barely ate, and other days when he binged on food. He stank and only came into the bathroom and toilet to empty his bladder and bowels.”

“His hair, beard, and fingernails grew long and unkempt, and he shut himself in this house, even forgetting to say his prayers,” Yasmina jumped in, continuing the tale, but she was interrupted by murmuring from the other walls. All of them seemed baffled that they don’t remember this event in the house.

“Or if I do remember such things, only quite vaguely,” said Zohra, “I wonder why.”

Then Lilia spoke out, not wanting to let Yasmina do all the talking. “Then one day,” and here Lilia’s voice started to break, and it seemed like she was about to cry, “Jalal came in the bathroom to hang himself and end his misery. Yasmina and I were so shocked, we were screaming, begging him not to do it. When he tied the rope on the wooden beam on the ceiling, and then the other end around his neck, as he prepared to jump from that stool, Yasmina and I didn’t know what to do.”

“Then,” Yasmina interjected, “I thought that it was already nearing winter and the cold was already creeping into the house. I remembered that when this happens, our friends, the wood and the stone can expand or contract, depending on how the cold affects them. So, I had this idea, and told Lilia to, you know, sort of push and wriggle against the house structure; we did this together with all our might.”

Mabrouk, the north wall, then exclaimed, “Hey, I felt that back then! I thought there was a slight earthquake. I never thought that it was the silly both of you.”

Yasmina, ignoring the silly comment, continued: “Well, all that pushing and wriggling loosened one end of the wooden beam. When Jalal jumped off the stool, the beam could no longer hold his weight and he fell. Thank God, he didn’t break his neck in the fall, and the wooden beam only grazed his scalp; I think I heard the wood apologize when it fell. Jalal had a bloody gash on his head, though.”

Lilia shushed Yasmina and continued the story. “Then, miracle of miracles, that was the day when his friend, the trader who survived the shipwreck, came to the house and he had brought Jalal’s wife along. They saw him unconscious and bleeding in the bathroom with the rope still tied to his neck.

“It was then that the friend and the wife took Jalal to a doctor to stitch up his wound; and the friend suggested to the wife something she didn’t expect: for Jalal to go to the island of Djerba to visit a holy shrine there, dedicated to the spirit of a little girl. The friend said that he himself had met this spirit; the little girl had, in fact, rescued him and his son after they were stranded on the island by the shipwreck. He also mentioned that a sheikh also lived on the island, who might be able to help Jalal. Then the wife said this to their friend:

‘Please, please take Jalal to Djerba. I always dreaded that this would happen someday, that my beloved would be stricken by some madness. You see, this sort of insanity runs in their family. His great grandfather was the first—that they know of—to go mad; it is told among his family that this great grandfather of theirs once visited this very place, while this house was still being built.

‘This great grandfather of theirs was obviously insane by then: he wanted the builders of this house to go and sacrifice children, telling them that such an act would make the foundations of this house much stronger and last longer.

‘If there’s a chance that Jalal would be cured by a pilgrimage to Djerba, then you have my blessing to take him there,’ the wife said.

It was Yasmina’s turn to shush Lilia. Yasmina then continued the story: “And, lo and behold, after being away for about two months, Jalal and his wife and daughter moved back here. He recovered completely and resumed trading. He also became a more pious man. He was really a gentle, kind, and generous sort of person.”

“Maybe that’s why he and his wife stopped their petty arguments,” said Ramla.

All the other walls breathed a sigh of relief over the happy ending for Jalal. They all expressed commiseration to Yasmina and Lilia for having had to witness Jalal’s actions in the bathroom, and they also commended the twins for saving his life.

Everyone then turned to Ramla for her story, which was:

–

Ramla’s Tale: The Wandering Jew and the Spear of Destiny

Before telling her story, Ramla, the west wall, told everyone that she herself never believed in such a thing as the Wandering Jew.

“I don’t have the faintest who that is,” said Mabrouk.

“Well, you ignorant, illiterate slab of rock,” replied Ramla, although she said this endearingly, as she loved to tease Mabrouk whenever she spoke to him, “the Wandering Jew is supposed to be this Roman soldier who was cursed to walk the earth until the Second Coming of Christ. This was because he was the one who plunged a spear into Christ’s side.”

“Wait,” Mabrouk said, confused, “was he Roman or was he Jewish? Get your story straight.”

“Hey, I didn’t make this story up. I’m just telling you what I heard. He was a Roman soldier when he allegedly speared Christ, and turned into the Wandering Jew afterwards. Practically immortal, at least until Christ comes back,” replied Ramla.

“Well,” Mabrouk said, “some might consider it a really bad curse to transform from a Roman soldier into a Jew.” To which Ramla responded, “Shush. Stop your racist comments, shame on you. All humans are God’s creatures regardless of their religion or creed. Shut your mouth already.”

Then everyone paused when they heard a soft snoring. Zohra had fallen asleep, as she was wont to do. At this, Othman, the house’s exterior wall, laughed. The entire house shook and this woke Zohra up. “I’m sorry, did I miss anything? Please go on,” said Zohra.

“All right,” Ramla continued her story, “if you still remember, there was one time when a Jewish family lived in this house. The father was a trader named Mimmi, and he specialized in antiquities and in religious and mystical artifacts. He had two sons, Simon and Levi who were in their teens back then. The one daughter was… hmmm, wait. She had an unusual name. Greek, I think. Ah. Rhea. Her name was Rhea. She was ten years old. Or maybe twelve. The wife’s name was Esther.

All the walls looked at each other but it seems only Ramla and Othman remembered the family. This wasn’t unusual. Walls remember stories and events in a house—but their memories are unlike that of creatures like humans, jinns, ifrits, or angels. Stories, events, memories, all settle and stick onto walls like dust and grime. And like dust and grime, these memories can be wiped off, eventually. The walls have no control over which stories, names, memories, details of incidents they remember. It’s not unusual for walls in a house to remember certain things and forget others, or for them to recollect their memories differently from one another.

“Ahem,” Othman, the exterior house wall, interrupted, “I believe I remember this Jewish family. When they stayed here, which wasn’t that long, there were all these shelves filled with supposedly religious and mystical objects that were sold to collectors and even people going on pilgrimages. But wait, this Jew was simply a dealer and supplier. He didn’t sell directly to customers.”

“I also remember that,” said Ramla, “and he also had books on the Kabbalah, and powders and potions, and relics of supposed saints, and magical scrolls, books of spells, essentially dealing in religious and occult objects.”

“Anyway, he wasn’t the type of overly devout or religious Jew. Though he wasn’t really a hardcore swindler either. He simply accepted that different people put their faith in different things, depending on their personal beliefs. And he was happy to deal in these religious, mystical, and occult items.”

“Still,” said Othman, “how many unicorn horns, how many finger-bones and ribs of saints could there be in the world? If all of those items were truly authentic, there would be no bones left of any saint to bury.”

“Anyway,” said Ramla, “one day this tall, muscular, stranger knocked at the door. It was the wife, Esther, who opened the door. She noted that the man, taller than her husband, and taller than most people in the medina, wore a dark tunic, what looked like military sandals, and a shawl was wrapped around his head and face, so that only his grey-green eyes showed.

Othman then interjected, “Then Esther asked, ‘And who might you be, sir?’ To which the stranger replied, ‘I am the Wandering Jew’.”

Ramla then spoke up, saying, “Hey, this is my story, quit interrupting.”

Othman replied, “I remember this story. Let’s tell it together. So that I won’t have to wrack my brains remembering a story of my own!”

Ramla, who was really a sweet, gentle, and generous sort, “Oh, all right, Othman. Go ahead, then. You tell the story. I’ll take a turn later—just don’t hog the whole story for yourself, you old bum.” But she was very sweet about it. And so, Othman continued the tale:

“Esther, who had not heard about the legend of the Wandering Jew, invited the stranger in, thinking that he was lost and homeless and needed some respite from his wanderings. When the stranger removed his shawl, Esther saw his entire face and remarked, ‘You don’t look Jewish.’

“She then called on her husband Mimmi the trader. Again, the stranger introduced himself as ‘The Wandering Jew’. This piqued Mimmi’s interest very much. So much that he asked the stranger to be so kind as to explain why he was called such. Mimmi had heard all sorts of strange, magical, and mystical tales, and even some crazy ones, and he was interested to learn a new one. He even asked if his children, Simon, Levi, and Rhea, could also listen in.

“The stranger looked at his audience, an entire Jewish family, and agreed. But first he said that he needed a pitcher of water and a cup. ‘You won’t believe how far and how long I have been walking,’ he said, and then greedily drank the water that Esther handed to him, emptying the pitcher forthwith. Esther had to go and get another pitcher of water, as it seemed like the stranger’s thirst hadn’t been quenched.

“And so, the stranger talked about the legend of the Wandering Jew, blah-blah, yadda-yadda, until he finally unpacked something to show Mimmi. It was a Roman spear; the stranger said its proper name is pilum, in Latin. ‘But,’ the older son Simon remarked, ‘the spear is broken in three places.’

“‘What do you expect,’ the stranger replied, ‘I’ve been carrying that thing around for hundreds of years. I had to break it apart to pack it more easily. Don’t worry. The shaft is irrelevant. It’s the spear head that’s valuable.’”

“Ahem,” Ramla interrupted Othman, saying, “Don’t hog the story, brother. Let me tell some more of it.”

“Sorry,” replied Othman, “Your turn.”

Ramla continued: “Then the younger son, Levi, said to the stranger, ‘Wait. You don’t even look like a Jew. You have a Roman nose.’

“To which the stranger replied, ‘Pray, tell, what in the world is a Roman nose? That’s nonsense. Long ago, I was called Longinus, and I carried this pilum with me all the time. But the Roman empire is fallen. I supposed I could be whoever I want. And today, I am a Jew.’

“Mimmi pressed on with his questioning, ‘You really went up to Jesus Christ and stabbed him on the side?’

“The stranger replied, ‘I stabbed someone hanging from a cross. There were more than one of those criminals crucified that day. At least six of them on that hill. I only stabbed him as a mercy; he seemed to be suffering more than the others, and I thought it better for him to die more quickly. I didn’t know whether he was one of those wandering Jewish preachers, or if he was a thief or murderer, or a zealot; I was only told, later, that some people were claiming that he was some sort of prophet, or was claiming to be the Jewish messiah. I really never paid attention to those things. Prophets, preachers, holy men, and messiahs popped out of the ground like mushrooms during those days.’

“‘But you said,’ replied Mimmi, ‘that you had been wandering the earth with this spear, and you would only die when Jesus Christ returns.’

“The stranger replied, ‘I have survived for hundreds of years since the day I stabbed that man on the cross. I have no idea why. I do not feel any different. My life has neither become worse nor better, although I have to keep this aspect of my nature secret, or else some ignorant mob would burn me as a witch.’

“Then Rhea, in a small voice asked, ‘Sir. Have you, um, have you, I mean, tried to die?’ Esther went red in the face and shushed the girl; feeling embarrassed, she apologized to the stranger. The stranger waved a huge hand dismissively, to say it was no big deal.

“The stranger looked at Rhea more closely, noting that she had red hair. Then, speaking directly to her, as though she were already a grownup, he replied, ‘Yes. Many times. I’ve tried. I even hung myself once, and then jumped from the top of a pyramid in Egypt. I broke my neck both times, and lived. It was excruciating, painful, to heal from a broken neck. I couldn’t eat properly. Imagine what it’s like to go hungry and be in pain for months, without eating? Imagine starving but being unable to die. That taught me a lesson: avoid injuries as much as possible.

‘One day, I decided that I would no longer carry this spear around. I had kept it for so long because I was hoping that one day, it would provide me with an answer as to why I can’t die. But I’ve given up. It doesn’t matter anymore. Despite living for so long, I have not tired of it; I have no intention of killing myself and I simply intend to live for as long as I’m destined to live.’

‘When I heard that a legend had somehow grown out of my spearing that crucified man, most likely a criminal, anyway, and that some now believe this spear to be holy or mystical, then perhaps I can simply get a good price for it from you. Sell it with the legend. You might get quite a bit of money for it, especially if you sell it to a Christian or even to a Catholic bishop. I think even the Pope would be interested in this.’

Then Othman interjected, “And that’s the day when Mimmi decided that, faced with the power of a real mystery, the possibility of a true immortal, and a man seemingly punished for killing a crucified criminal; Mimmi resolved that he was more than just a seller of artifacts, relics, and curiosities. He somehow thought that apart from the relics themselves, it was the stories behind them that gave them value. The stories provided the power of belief and faith, and the physical artifacts were simply baubles that gave these stories the barest semblance of reality.”

Ramla smiled, not minding how Othman interrupted her again. She breathed in and out, and finished her tale with this:

“And so, Mimmi the Jewish merchant took the spear, and paid quite handsomely for it. Later, he embellished the legend and called the spear names like ‘The Holy Lance’ and ‘The Spear of Destiny’. And not only that. He asked a blacksmith to make two copies of the spearhead, and sold all three as the original Holy Lances that poked Jesus to different buyers.”

“He shed off all scruples about the authenticity of his artifacts. For him, it was the stories that mattered more. So, what if he had in his shelf the so-called ‘last true unicorn horn’ in the world? He worked with Simon and Levi to make five more ‘last true unicorn’ horns; they sold these to various buyers.

“Finally, Mimmi also acquired three pairs of sandals, each one older and more wornout that the other. He was selling them as ‘The Sandals of the Wandering Jew’. He also crafted the legend behind them more properly. The Wandering Jew was either a passerby who insulted Jesus Christ as the latter was carrying the cross to Golgotha Hill, or the Wandering Jew was a doorman at the Roman governor Pontius Pilate’s residence, who mocked Jesus Christ as the latter left Pilate’s presence. As punishment, this Jew was cursed to wander the earth until Christ’s return.

“One night, as the couple was about to go to sleep, Esther asked Mimmi, ‘You have invented such a tall tale. As ridiculous as the one about The Spear of Destiny. Who would believe such stories and spend good money on those ugly, old sandals?’ Then Mimmi yawned and replied, ‘Christians’. Then the couple went to bed. Less than a year later, their entire family left this house to move into Medina’s Jewish quarter, The Harah,” said Ramla.

All the walls gathered in storytelling fell silent, perhaps contemplating the strangeness of humans and their attachments to trinkets, baubles, and other material things. Then Mabrouk, the outermost and most massive wall that surrounded all of them, cleared his throat, saying, “I believe it is my turn.”

–

Mabrouk’s Tale: The Curious Clash of the Hen and the Goat

Everyone felt a tinge of anticipation as Mabrouk, the north wall, braced himself to tell his story.

“For many weeks that have passed before this night, I have heard some disturbing news. Explosions. Deaths. Bombs falling from aircraft. Artillery rolling inland from the coasts. The humans are at war once again, dear friends. Why, just yesterday, I heard a distant crashing and shattering, walls howling in pain and fear—the word that’s been passed on outside is that a bomb was dropped onto a railway station. Fortunately, no one was killed.

“Through my hundreds of years protecting our compound, this is the only time when my confidence has been shaken. I am built massively and strong to withstand many onslaughts by nature and by man—as was the intent of Ismail and his crew of eight jinns, ever since the very first section of my structure was erected on the night the archangel Jibril faced off and drove away the Beast of Iblis’ (Curse Him)Rage.

“Ooooh,” Lilia squealed, “So you were born on that day! Wow. You’re even older than oummi Zohra!”

“Of course, I was, child. You twins are only seventy years old, so I forgive your interruption,” replied Mabrouk with a grunting harrumph in his voice. But he was only kidding, being quite fond of the young walls in a paternal way. “Anyway, as I was saying, the weapons of destruction that men are unleashing into this world are simply too powerful. I can only pray to Allah (Praise Him) that no bomb, no artillery fire, and no tank missile ever comes near us as this war progresses. And let us all pray for this war to end.

“Enough of these worries. I want to tell you about something that happened outside this very house, many years before Al-Hajj Mohamed took up residence. This incident happened for two nights in succession, right outside my western flank.

These incidents happened after the stroke of midnight each time. It all started on a Sunday, past midnight, years ago. Everyone was asleep of course, and I was, as usual, quite awake and alert for any miscreants. There was a curious groaning, hissing, feral rasping sound in the darkness, coming from the shadows along the walls of the narrow road leading to this cul de sac.

“I thought it was some sort of rabid dog, or even a large rabid rat, as it was crawling on all fours and sniffing its way about in the dark. Then, to my surprise, the creature stood up all of a sudden on two legs, and broke into a run, growling, gnashing its teeth. It looked somewhat like a man, was dressed in tattered clothing, and seemed more dead than alive because it stank like a corpse; its eyes were a sickly green, and seemed to glow like a luminescent golden pus. The hairs on its head were long and bristly, and these all stood up like spikes.”

“Oh, so horrid,” said Ramla, “what in the world was that?”

“You’ll find out later,” replied Mabrouk. “This creature looked ravenous as it kept snapping its huge jaws; its teeth looked gnarled but sharp, like a hyena’s. It had no nose to speak of, only three nostrils that looked like slits. Then, just moments after it burst into a run, it crashed right smack onto my western flank. Of course, strong and ferocious as it was, it could not breach through me; it might have broken several bones upon slamming into me but still, it clawed at me with its sharp fingernails. Then, finally, exhausted and perhaps even injured, the creature stopped and crawled, slinked back into the dark.”

“Dear saints in heaven,” exclaimed Zohra, who had become too alarmed to doze off, “we should warn the household! There might be more of those things out there!”

“Please, please calm down, oummi Zohra,” said Mabrouk, “Let me finish the story first. So, that happened on the first night. On the second night, at nearly the same time, another creature, quite like the first one, appeared. This time, however, it seemed less feral and less ferocious. It seemed to be more… intelligent?

“Instead of charging right at me, this creature stalked outside until it reached the massive, think double-leaf main door up front. It slid its hands across the door, as though it were trying to determine how thick and strong the wood was, and whether there were weak spots. After this, it growled, seemingly in frustration. I thought it was going to leave by then, but instead it whistled; it sounded like one of the common chirps of night birds, nothing suspicious nor menacing about its sound. However, that whistle drew in two more of the creatures.

“These two monstrosities seemed less intelligent, and seemed to shamble slowly towards the one that whistled to them. One of the creatures, the smaller and thinner one, was carrying a basket—the sort that is used to carry eggs or even a chicken. As it got closer, I saw that the basket indeed had a chicken inside, a huge, black hen. The smaller creature then walked right beside the first creature, the whistler, and set the basket down. Closely following it was the third creature, also more feral, but this was much bigger, like a bull walking on two legs.

“Then,” Mabrouk paused, as though his throat had gone dry and he was trying to swallow. There was real fear in his voice, this time.

“The first creature, the whistler, said something to its monstrously bull-like companion. I have no idea what was said, since they spoke in grunts and rasping barks. But the bull-like creature seemed to not like what the whistler said. It bared its teeth and growled angrily, sticky spittle spraying from its jaws.

“At this, the whistler raised one eyebrow and fell silent. Then, it struck out with its hand, an open palm strike, smashing a massive blow to the side of the bull creature’s face. The bull-creature was thrown far to the side, onto the ground. Green pus-like matter dripped from the side of its face. It looked beaten and defeated, managing only to make choking noises, and short, pleading howls. It sat upon the ground, then looked towards the whistler and nodded.

“The smaller, thinner creature then grabbed the black hen from the basket. The creature then breathed its foul breath upon the hen. Strangely, the hen afterwards went limp; it looked groggy, drugged, or entranced. Its eyes drooped and seemed in a daze. The smaller creature then threw the hen at the injured bull-creature, that was now on the ground, sitting.

“The bull-creature then began to eat the hen alive, the way a serpent would: the bull-creature opened its jaws massively wide, and pushed the hen into them with its hand. In a few moments, the hen was gone, swallowed whole, feathers and all. After this, the bull-creature doubled over in pain. Its limbs began to twist, and popping and cracking sounds came from inside its body; it’s huge ox-like physique seemed to crumple and the creature fell on the ground, wracked by seizures and spasm. Then, incredibly, it began to change.

“It changed its size and form, until before I knew it, it had become an exact duplicate of the hen that it had consumed whole earlier. It acted exactly like a hen, strutting and clucking about. The smaller creature then went to the hen, grabbed it—and not quite gently—and placed it inside the basket. The basket and hen were placed right beside the double-leaf door. The smaller creature shuffled away and disappeared.

“The whistler then called out through the door, making a different sound. It cackled loudly, like a hen. Of course, no real hen would ever cackle so loudly; but the creature was mimicking a hen’s cry to call the attention of the people inside the house. Finally, one of the maidservants, you might remember her. Her name was Hend. At the time she was rather young; only nineteen years old. She opened the door of her room and went outside. She crossed the courtyard, obviously confused as to what the noise was about, and made her way towards the double-leaf door.

“By the time she opened the door, none of the creatures were in sight, and she only saw this innocuous-looking black hen sitting plump in its basket. The maidservant then thought, ‘What’s this? Someone must have left this for our master. But why at this hour? Well, I’ll show him this first thing tomorrow.’ And then the maid took the black hen in and shut the main door.

“As the maid started to walk back across the courtyard to leave the basket and hen at a suitable place, there was a loud knock on the main door. Blood rushed to the maid’s face in irritation—whatever sleepiness she had a while ago had disappeared-and she exclaimed, ‘Oh, what now?!’ But then she thought that maybe it was the same person that had left the hen by the door—perhaps someone that her master knew. So, still with the basket and hen in hand, she walked back to the main door and peeped through the small opening of the door—something that she ought to have done earlier had she not been rudely awakened and half-asleep—to see who was knocking.

“But there was no one that she could see through the slot. Then a man’s voice spoke, and called out her name, ‘Hend, please. Open the door. I must take that black hen back where it belongs. It should not have been left here.’ Hend thought that the voice sounded familiar.

“She then spoke to the man through the opening, ‘Sir, who are you, why are you here at this time?’ Then the male voice answered, ‘My profuse apologies, Hend, but I’m a bit preoccupied over here, I cannot come to the front where you can see me. Please let me have that hen back.’

“Hend could no longer contain her bewilderment over what was happening, so she opened the door and stepped outside. What she saw both surprised and puzzled her. She saw a large goat—it was huge, with a long thick brown coat, and massive horns. The goat’s great front hooves were stepping on the back of what seemed like an unconscious ape.

“Hend’s mind was still trying to understand what she was seeing, when suddenly, the goat spoke to her. The man’s voice she heard, that had spoken to her from the other side of the door earlier—it was coming from the large goat. ‘This is serious, Hend! Please throw that basket to me, NOW!’ the goat yelled at her.

“Being yelled at by a talking goat was too much for Hend’s mind. Instinctively, she threw the basket with the hen at the goat, but it was more out of alarm and partly to shoo the goat away. The basket clattered on the ground and the black hen awkwardly strutted and flapped its wings, moving in a zigzag pattern, clucking away, as though it was just as bewildered as Hend over what was happening.

“Then the goat yelled again, ‘Hend, go back inside and shut the door! Now, now!’ Her mind in a panic, Hend simply obeyed the talking goat. After closing the massive main door and bolting it shut, Hend dropped to her knees, still panicking. ‘The goat was talking to me. It was talking!’ she told herself, and then she fainted straightaway.

“The goat then spoke to the black hen with an edge to its voice, in a menacing tone, ‘Fiend. Monster. Get away from this house. This house is under my protection!’ At these words, the black hen seemed to snap out of its bewilderment and seriously regarded the goat. It clucked more violently, until its clucking became a guttural snarl. Suddenly, the hen’s body puffed up, seemingly growing muscles underneath, and several of its black feathers even popped off, dropping to the ground.

“The black hen, now grown to be as big as a large hunting dog, or a hyena, opened its beak, revealing its frightening, jagged teeth. It looked like some demonic fowl, its eyes glowing green. It rushed at the goat, flapping its great black wings, its feet now turned into razor sharp talons.

“But the goat was ready. It side-stepped and the black hen ended up digging its talons into what Hend thought was an unconscious ape. In reality, though, the unconscious body was that of the smaller creature that had brought the chicken there in the first place. The black hen, having missed its target, grew even more enraged. It growled more fiercely and then enlarged its body even more, until it was the same size and form as the bull-creature that it really was. Its chicken wings disappeared in a puff of black feathers, replaced by gargantuan arms and hands with sharp nails. However, its head was still in the shape of a chicken; a massive black chicken’s head with a huge beak, and scary teeth.

“It rushed at the goat again, and this time, the goat came towards the bull-chicken-creature at an angle, ducking and avoiding its massive arms; the goat’s horns stabbed the creature’s side and went in deep. The bull-chicken-monster screamed in pain. Then the goat shook its head and pulled away, leaving the monster bleeding with sickly green blood.

“There was a flash of light and the goat transformed. It was Ismail the jinn, after all. In his right hand, he was carrying a sledge hammer—the kind used for smashing rocks and concrete. He ran towards the bull-chicken-monster—it was an incredibly swift movement—and swung the hammer in an upward arc, in a two-handed grip, slamming the hammer’s head into the monster’s face. The bull-chicken-monster was lifted off its feet, and fell several yards away. It was dead, as far as I could tell.”

“That’s, that’s…” Ramla began to say, “bloody amazing. I mean, what a terrifying fight. But what was that all about?”

Mabrouk sighed and said, “Exactly my own thought, after I saw it”. Mabrouk continued his tale after a brief pause. “I couldn’t help myself after what I witnessed. I yelled at Ismail, saying, ‘What just happened? What are those monsters? Why were you a goat?!!’”

“Then Ismail turned to me and said, ‘Be patient, my friend. I must get rid of these monsters’ disgusting remains, and I must see to it that Hend is all right. Poor girl.’ It was only then that I truly witnessed how fast a jinn could move. In an eye-blink, the remains of the monsters were gone. And, as Ismail told me, he had tucked Hend right back in her bed.

“Only then did Ismail explain to me what happened. According to him, this latest war among the nations of men has unleashed many evils into the world. Among these evils are the ghouls that are able to change their form. Specifically, they can change into the form of whatever unfortunate creature—man, animal, or insect—they recently ate. This is why that monster had to eat a black hen first before it could shape-shift.

“As Ismail told me: ‘Ghouls are powerful and malevolent. The most evil ones have a hunger and greed that are never satiated. They are creatures of pure carnal and carnivorous appetite, and they are top predators. However, ghouls can be killed by the weapons of man, as long as the fatal blow is dealt to their heads. They can also be killed by fire. And yet, their powers of transformation and disguise make them deceitful, dangerous enemies indeed.

“‘There are several types of ghouls my dear Mabrouk. The whistling ghoul, for example, is intelligent, a planner and a strategist. It naturally takes on leadership roles. And its kind are not slaves to their ghoulish appetites. This makes them more patient, more cunning, more dangerous. The gargantuan, muscular ones are more feral, and wild, but still retain some intelligence. They function as warriors, soldiers, and attack beasts; yet, they can be stubborn. The weakest among them are the smallest among their ranks. These are like slaves that perform menial work—but make no mistake, they can still kill and eat other creatures. All three types of ghouls have shape-shifting powers.

“‘Obviously, Mabrouk, there was a plan to sneak into this house through cunning means. Had your maidservant Hend left that black hen inside the house, who knows who it was supposed to kill and consume? But of course, the true plan and motive is only known to that whistling ghoul. I and the other jinns guarding this house must be more vigilant.”

Then Mabrouk expressed his concern to the jinn builder: Are there more ghouls out there? Wouldn’t they return and try to accomplish whatever mission was foiled tonight? All that Ismail could say, in reply, was that he and the other jinns would be keeping watch. ‘Ever since this great world war among men began, we have been wary and watchful of these ghouls. We don’t know why they have suddenly taken an interest in Tunis, and why they are gathering here in force. Just be assured that I am here along with my jinn friends to protect this house and its residents.’

“Then I asked Ismail the question that had been bugging me like a fierce itch,” Mabrouk said to the other walls. “I asked Ismail, ‘Why dear builder, why? Why were you a goat?’

“Ismail looked at me incredulously, as though I had asked a stupid question. Still, he answered me: ‘Dear Mabrouk. I cannot go around either by day or by night in my true jinn form. Neither could I walk these streets after midnight as Ismail the Builder and perfume trader. What would people think I was up to?’

“So, you decided that a large talking goat is a better disguise?” I asked Ismail back. The jinn builder looked a little miffed at my question, and I felt that I may have offended him. Still, to his credit, he patiently explained the matter to me:

“‘My dear Mabrouk. I obviously did not wish to go out and about speaking like a man while in goat form. But I had to warn Hend right away. The black hen, that bull-sized ghoul, was already inside your house. And I had just subdued the smaller ghoul. I was in goat form tonight because I am not very good at shape-shifting; I only have a few disguises and most of them are in human form. Like I said, it is more suspicious to see a man wandering in the dead of night, compared to a goat. Even the ghouls do not openly walk these streets, choosing to disguise themselves as animals, too. After all, humans can still harm and kill them if they are found out.’”

“My, my, my”, Zohra interjected, “Such ghastly things are afoot during these terrible times.”

Mabrouk continued his tale: “And after Ismail explained those things to me, he bid me farewell. I told him to take a shower because he stank like a goat.” At this, all the walls broke out in laughter—but then, from a distance, they heard the whistling call of a night bird, and they all fell silent.

–

Tea and morning prayers

The walls all had a splendid time, swapping and sharing stories, and they did not notice that morning was about to break. Then Zohra shushed all of them, saying, “Wait a minute. Khemais and his father are still in the kitchen, still talking. I’d like to listen in. Let’s all listen to them.”

The father looked at his son. There were dark circles around his son’s eyes, and his face looked gaunt and pale. It was a sad sight, what the illness did to him. How the recurring nightmares seemed to ravage both his son’s body and spirit. Al-Hajj Mohammed was not much of a talker, and he seldom openly displayed affection to anyone—most of the time he had a stern, severe aura that made others tread carefully, so to speak, in his presence. But somehow, this night, he was able to talk quite a bit with his son.

Then Khemais took a deep breath and sighed. Without looking at his father, Khemais put his face in his hands, and his entire body shook and shivered. He wasn’t crying, but he was obviously distressed. He then told his father about something that had been troubling him all these years, even before he met and married Wassila. He began with, “Baba. Do you remember the day when an aerial bomb hit the railway station where I worked?”

“Yes, of course,” replied Hajj Mohamed. “I thank Allah (Praise Him) that you survived that day.” Then Khemais said, “The fear, shock, and dread of the experience has never left me. And, during this long illness, the memory of that bombing has been the stuff of my nightmares. It was most probably the Germans who dropped a bomb on the railway station. Thank Allah (Praise Him) that there was no one at the station platform and at the office. I had left the office and had gone into the outhouse to relieve myself.

“Then suddenly, there was a loud explosion, a rush of hot air, and I was thrown off my feet. I found myself outside the outhouse, on the ground. Most of the outhouse was demolished. I looked at the railway station and it was a smoking ruin. It’s a miracle I’m alive,” Khemais told his father, and then his body shook uncontrollably. He tried to take a sip of tea but his hands were trembling so much that the teacup also shook and some of the tea spilled on the table.

Despite his stern and severe disposition, the father, Hajj Mohamed, found himself hugging his son, kissing the latter’s cheeks and forehead. “It’s all right now, Khemais. You are all right. You are safe. I thank Allah (Praise Him) that He has brought you back to me, to your mother, to your brothers and sister. He brought you back from the brink of death. He saved you from that bombing so you could meet Wassila. So you could have a son, and I, a grandson. I know in my heart that Allah (Praise Him) has a purpose for everything. He has a purpose for you. He granted a new life not only to you but to Wassila; and, through Abdeljabbar—He granted new life to our family. Let us not waste His gift of life. Come now, breathe. Wash your face. Let us finish this tea and then say our dawn prayers.”

All of the walls were in tears; well, not that any human would have noticed. It was the dawn of a new day.

______

Illustration by Stephen V. Prestado